Osteosarcoma of the Extremities: A Retrospective Study on Statistics & Histopathological Implications in a Single Centre Data

Osteosarcoma of the Extremities: A Retrospective Study on Statistics & Histopathological Implications in a Single Centre Data

Eyrique G *1, Tee KK2, Tham JI 3, Aaron G Paul4

1. Orthopedic Oncology Unit, Orthopedics & Traumatology – Hospital Queen Elizabeth 1&2, 88586 Sabah Malaysia

2. Pathology department - Hospital Queen Elizabeth I & II, 88586 Sabah Malaysia

*Correspondence to: Eyrique Goh Boay Heong, Orthopedic Oncology Unit Hospital Queen Elizabeth 1&2, 88586 Sabah Malaysia.

Copyright

© 2024 Eyrique Goh Boay Heong. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 12 July 2024

Published: 01 Aug 2024

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13142698

Abstract

Osteosarcoma is a common bone malignancy leading to morbidity and mortality. Osteosarcoma is a malignant tumour of connective tissue origin within which the tumour cells produce bone or osteoid material. This is a retrospective study of Queen Elizabeth I & II Hospital Sabah Malaysia – all Osteosarcoma cases from 2018 to 2023 (a 5 years single centre study). These are patients that are registered and managed between 2018 to 2023 and are still followed up at least 6 months from initial diagnosis and had undergone surgery. Here we analyze the statistics and the histopathological implications of these patients, We look into age, gender, distance from residence the institution, laterality, anatomy involved and presence of metastasis. We also analyse into the histological implications namely the grade, types and its subsequent treatment modality giving a clearer image on the Osteosarcoma distribution in Sabah Malaysia. There are significant limitations to this study. Due to the unequal duration of follow up & poorer patient compliance from diagnosis to treatment to follow up, some patients were lost and could not be reached. However in general, Osteosarcoma patients in our institute were effectively treated in accordance to national guidelines, in a 5-year overall statistics. The prognostic factors found in the current study cannot be predictors of significance on survival. More research is needed on the cause of osteosarcoma and its progression, the role of genetics, better testing options for earlier and more accurate diagnosis, and treatments that can reduce patient morbidity and mortality.

Osteosarcoma of the Extremities: A Retrospective Study on Statistics & Histopathological Implications in a Single Centre Data

Introduction

Osteosarcoma is the most common bone malignancy in the paediatric and adolescent age group leading to morbidity and mortality. Surgical resection of the tumour remains the gold standard treatment followed adjuvant therapies (1). Survival rates had improved due to the advent advancement of chemotherapy (1). In literatures, 5-year event-free survival (EFS) rates between 55 to 75% had been reported (1- 2), and recurrence occurring approximately 30 to 40% in patients with localized disease, despite a complete surgical resection of the primary tumour and adjunct chemotherapy regimens. These findings reveal an important need to clarify prognostic factors for recurrence or poor survival.

Currently, several studies have already been identified on clinical or pathological features associated with undesirable outcome (3). Several data demonstrated a significantly reduced but homogeneous number of cases of limited statistical significance (2). Moreover, various research studies from multi-centres differs in data collection and therapeutical regimes and protocol making it difficult to compare and reveal contradictory results.

The definition of osteosarcoma is a malignant tumour of connective tissue (mesodermal) origin within which the tumour cells produce bone or osteoid material. Although this makes it seem as though the cells giving rise to osteosarcoma must be of osteoblastic derivation, there is no evidence that osteoblasts, once they differentiate from osteoprogenitor cells, can actually revert to more primitive cells, let alone malignant ones (4). Historically surgical biopsy was the first-line technique for musculoskeletal tumours, providing an adequate tissue specimen for further histopathological assessment. However globally we had moved towards a more micro approach which popularized the core needle biopsies. Sample volume plays a significant role in the result accuracy (5). This study will also analyse the pre-operative biopsy versus definitive resection biopsy and its implications.

In Malaysia let alone state statistics - Sabah, no published studies in defining prognostic factors for osteosarcoma, which is essential to improve the development of new and adapted strategies according to risk groups so as to improve survival rates.

The objective of this present study is to define clinical, and pathological features, as well as to report statistics with its histopathological implications affecting outcomes among oncology patients diagnosed with high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremities in the state and the institution.

Methodology

This is a retrospective study of Queen Elizabeth I & II Hospital Sabah Malaysia – all Osteosarcoma cases from 2018 to 2023 (a 5 years single centre study). Based on manual medical records from January 2018 - December 2023. Orthopedic Oncology unit had started services here in Sabah from 2013 to currently - about 10 years. As complete tracible documentations with significance are from 2018. The sample size of this study is restricted to within 5 years. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 disrupted treatment and follow-up.

The inclusion criteria are as follows:

a) Historically diagnosed as primary osteosarcomas – with histopathological confirmation and validated.

b) Complete basic data information

c) Patients with or without lung metastasis

d) Those agreeable for treatment and had commenced their treatment in the institution

e) Had both initial and definitive biopsies with formal reports

Patients who are excluded are those that cannot be followed up or those whose definitive biopsies are not consistent with the definitive biopsy result of Osteosarcoma.

The variables involved are as follows: age (less than 18, 18 – 40, more than 40), gender (male or female), tumour site and laterality, surgery (conservative, limb salvage, amputation), tumour necrosis: based on concept of Huvos classification – (Less than 50%, 50-90% & more than 90%), distance in kilometres (km) from residence to the institution, lung metastasis, similarity of the initial and definitive biopsy.

Lung metastasis was diagnosed radiologically, either by Chest X-rays or CT Thorax for nodules larger than 1 cm. Synchronous lung metastasis is defined as lung metastasis that is diagnosed concurrently with the presence of primary osteosarcoma while metachronous lung metastasis is defined as the occurrence of lung metastasis in patients later on follow-up.

As for localised osteosarcoma, neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy was performed per national guidelines. These patients in Sabah are treated with standard first-line neoadjuvant chemotherapy with MAP regime consisting of high-dose methotrexate, Cisplatin and Doxorubicin. The protocol dictates a standard 3 cycle doses of chemotherapy – subsequently a wide excision either limb salvage or amputation with the continuation of another 3 cycles of the chemotherapy. In cases of recurrence or refractory diseases, a combination of etoposide and ifosfamide (IE) is administered. The efficacy of the chemotherapy regime is reflected by the percentage of tumour necrosis during the definitive resection.

In these 5 years, the boney defect post-wide local excision, there are several surgical reconstructive options performed, namely endoprosthesis reconstruction, and modified methods of reconstruction: recycled autografts, composite allografts and cement spacers.

Result

Patients with Osteosarcoma were reviewed in our institution in Kota Kinabalu Sabah, the main centre managing patients with Osteosarcoma state-wide (Sabah, Malaysia). These are patients that are registered and managed between 2018 to 2023 and are still followed up at least 6 months from initial diagnosis and had undergone surgery.

|

Total patients |

|

N=30 |

|

Gender |

Male |

16 (53%) |

|

Female |

14 (43.3%) |

|

|

Age |

<18 years old |

15 (50%) |

|

18 - 45 years old |

13 (43.3%) |

|

|

>45 years old |

2 (6.7%) |

|

|

Distance from Centre |

Within city |

8 (26.7%) |

|

<200 km |

17 (56.7%) |

|

|

>200 km |

5 (16.75) |

|

|

Laterality |

Left |

24 (88%) |

|

Right |

6 (125) |

|

|

Location of OS |

Humerus |

2 (10%) |

|

Radius |

1 (3.3%) |

|

|

Femur |

16 (60%) |

|

|

Tibia |

6 (26.7%) |

|

|

Metastasis |

Yes |

24 (80%) |

|

No |

6 (20%) |

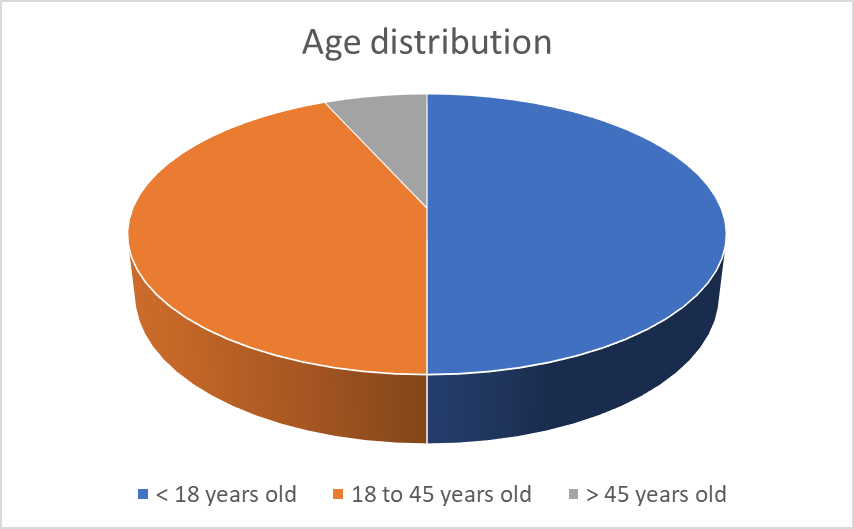

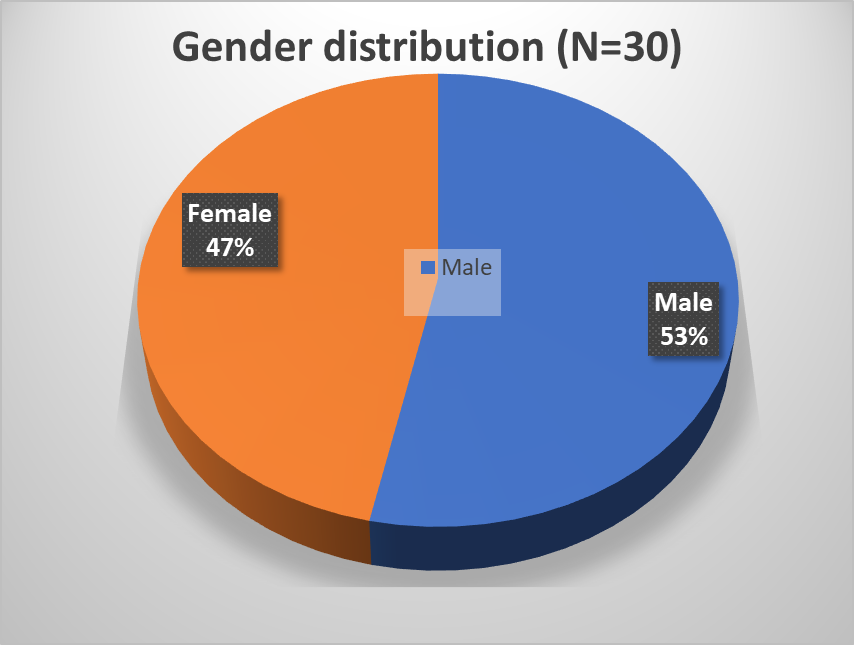

A total of 30 patients were identified with clear metastatic status with both completed histopathological report from the initial biopsy and definitive results. The average age at diagnosis was 21.17 (11 to 51) years. 50.0%(N=15) was less than 18 years old, 43.3%(N=13) was between the age of 18-45 and 6.7%(N=2) were >45 years of age. Of the 30 patients, Males were 56.7%(N=17) and Females were 43.3%(N=13).

Figure 1: Age distribution : <18 years of age, 18-45 years old, >45 years old

Figure 2: Gender distribution – Male 53% vs Females 47%

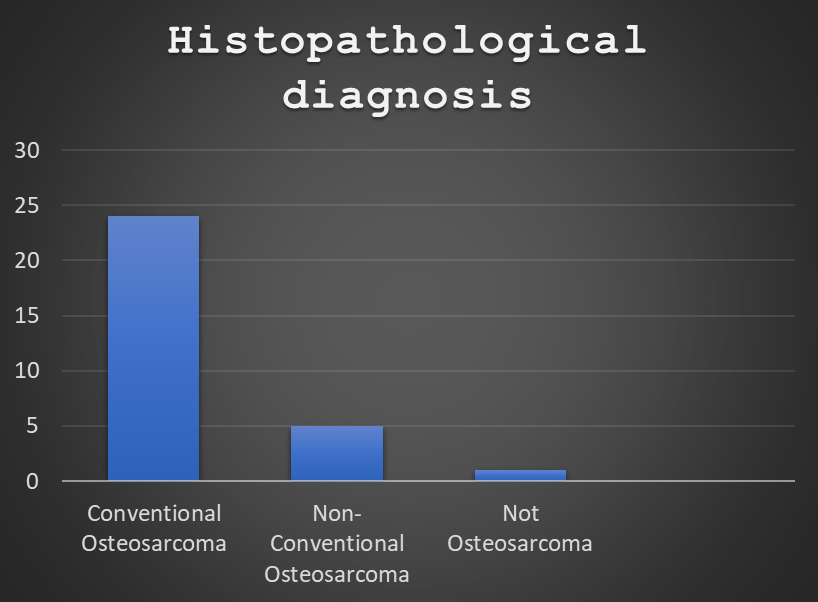

The histological types were described as Osteosarcoma (N =30), Conventional (N=25), Non-conventional [others] (N=4) and Non-OS in either of the 2 biopsies (N=1). All the OS tested were of High grade except for one which resulted in Osteomyelitis (N=1). All of the patients with OS underwent chemotherapy on various regimes as determined by the in-charged oncologist. As Kota Kinabalu is the sole referral centre handling Orthopedic oncology cases, we received patients from all over the state. Patients are categorized within the state of Kota Kinabalu 26.7%(N=8), within 200km range 56.7%(N=17), for example of Panampang & Kota Belud and those from more than 200km 16.7%(N=5), for example, Tawau and Sandakan.

Figure 3: Histopathological reporting for type of Osteosarcoma. Non-conventional osteosarcoma comprises of all other types of OS, for example: Chondroblastics, Parosteal, Periosteal, Telangiectatic etc.

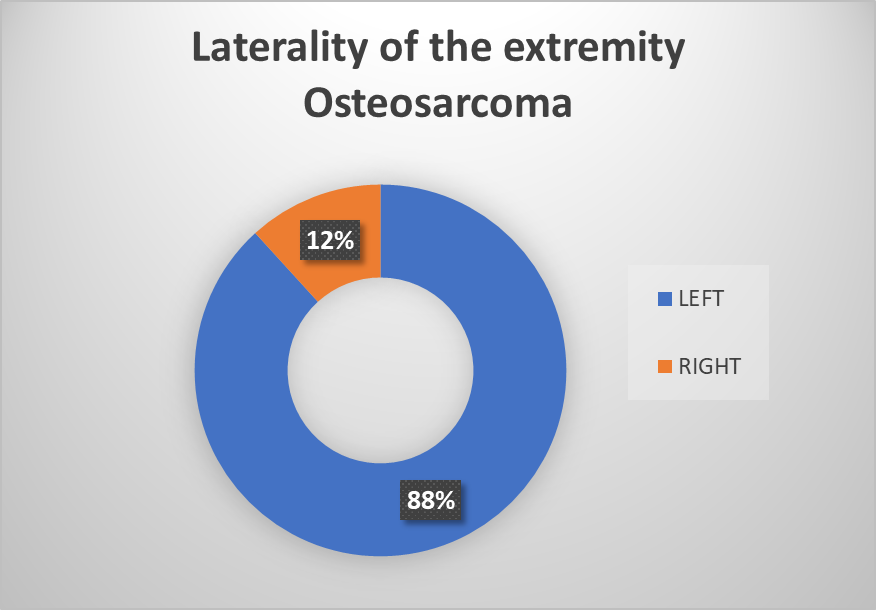

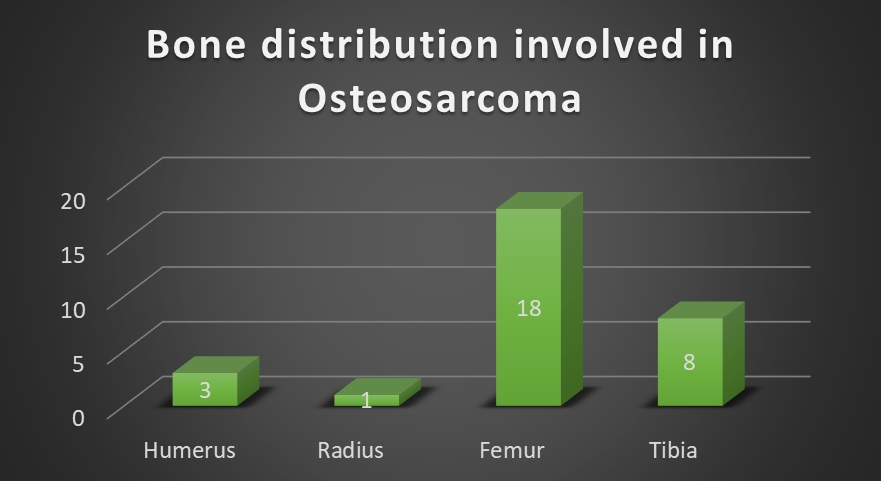

Of all the cases, the Left distal femur OS is the most common encompassing 50.0%(N=15) of the cases. Most of the OS were left-sided 80.0%(N=24) as compared to the right 20.0%(N=6). The bone involved from the sample were the humerus 10.0%(N=3), radius 3.3%(N=1), femur 60.0%(N=18) and tibia 26.7%(N=8).

Figure 4: Laterality involved of the extremity Osteosarcoma

Figure 5: Bone distribution involved in Osteosarcoma (N=30)

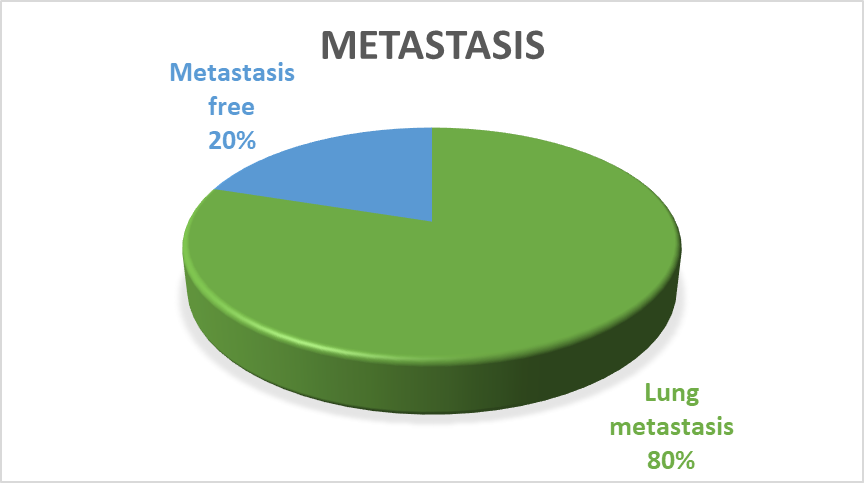

Of all the MRIs that were taken before the biopsy, all 30 of them reported as radiologically features Osteosarcoma. As 2 histology was taken from each patient, diagnostic biopsy and the definitive histology from definitive surgery. 93.3% (N=28) of the samples, both the reports confirm Osteosarcoma as the diagnosis, only 2 of the patients 6.7%(N=2) had the initial or final histology that differed – one was Ewing’s sarcoma and the other was Osteomyelitis in the definitive histology. 80.0%(N=24) were reported to have metastasis to the lungs via CT thorax either at diagnosis or eventually over the follow-up, and 20.0%(N=6) were reported to be metastasis-free as of April 2024.

Figure 6: Metastasis distribution in patients with Osteosarcoma

Table 2: Histological implications of Osteosarcomas

|

Total patients |

|

N=30 |

|

Osteosarcoma type |

Conventional |

25 (83.3%) |

|

Non conventional |

4 (13.3%) |

|

|

Not Osteosarcoma |

1 (3.3%) |

|

|

Grade |

High (100%) |

|

|

Tumour necrosis |

< 50% tumour necrosis |

18 (60%) |

|

50-90& tumour necrosis |

11 (36.7%) |

|

|

> 90% tumour necrosis |

1 (3.3%) |

|

|

Margins |

Clear |

26 (86.7%) |

|

Involved |

4 (13.3%) |

|

|

Lympho-vascular invasion |

Yes |

4 (13.3%) |

|

No |

26 (86.7%) |

|

|

Neurovascular invasion |

Yes |

5 (16.7%) |

|

No |

25 (83.3%) |

|

|

SATB2 stained positive |

Stained |

15 (50%) |

|

Not done |

15 (50%) |

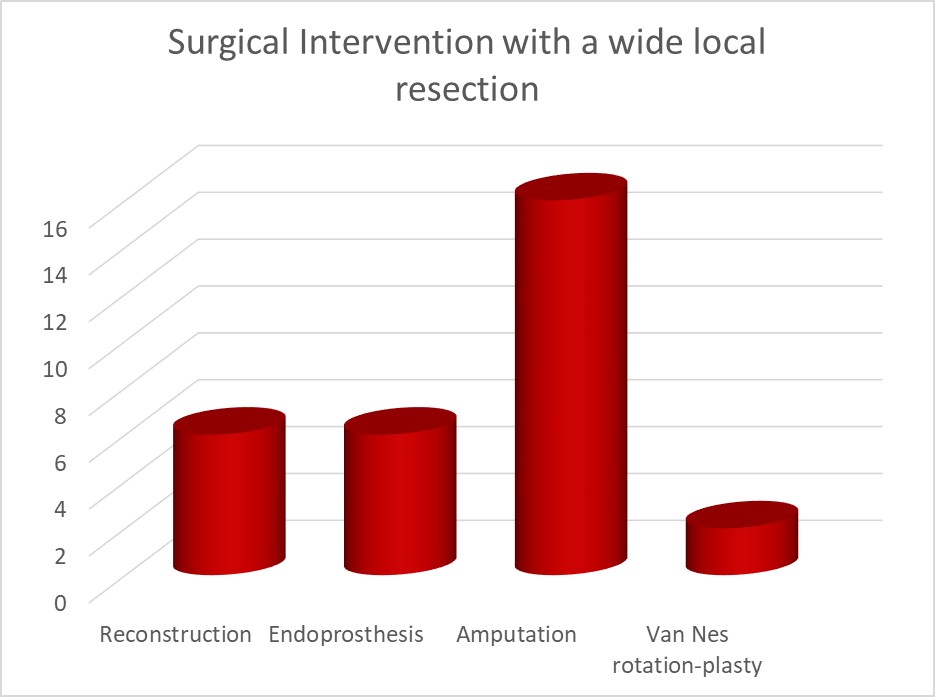

The tumour necrosis was analysed in the definitive biopsy and it varied in the range of 3% to 97% (with an average of 29%) – after neoadjuvant chemotherapy of 3 cycles with a minimum of 21 days prior to surgery. Tumour necrosis were classified into 0-50%(N=18) – 60.0%, 50-90%(N=11) – 36.7%, >90%(N=1) – 3.3%. All the patients went through surgery post 3 cycles of chemotherapy, The surgical interventions that the patient underwent were divided into Wide resection and Endoprosthesis 20.0%(N=6), Amputation 53.3%(N=16), modified reconstruction with bone cement 20.0%(N=6) and Van Nes Rotation-plasty 6.7%(N=2).

Figure 7: Tumour necrosis – analysis from definitive biopsy

Figure 8: Surgical intervention with mandatory wide local excision principle.

Most of those with amputation are due to Neurovascular invasion or significant tumour extension to surrounding structures. 16.7%(N=5) of the OS were reported to have neurovascular invasion either histologically or radiologically in the MRI. 13.3%(N=4) reported histologically with lympho-vascular invasion. 50.0%(N=15) of the samples were stained with SATB2 and reported as positive, None that were stained were reported back as negative – but not all of the samples were stained with SATB2, as it is highly selective, dependant on the stock availability provided to the institution. 20.0%(N=6) of the cases presented with recurrence and were managed accordingly, some had re-surgery and others that had died secondary to the tumour progression, however no complete documentation on the patient’s outcome. 23.3%(N=7) of the cases were complicated with infection and were managed either with antibiotics alone or with surgery. One patient was biopsied initially and reported as a classical OS, but during the definitive surgery the histopathological reported as Ewing’s Sarcoma with the presence of small round blue cells.

Discussion

In this current study, we summarized our experience from a 5-year data of 30 patients confirmed with osteosarcoma between 2018 and 2023, including the period of the Covid19 pandemic between 2020 to 2021. The presence of metastasis was associated with worse survival in osteosarcoma patients. Since the 1970s, the introduction of chemotherapy has significantly improved the patient’s survival, where later significant development and innovation in surgeries and comprehensive treatment (6). More research of margins over the years has enabled better and more Limb salvage surgeries. Chemotherapy and the references on the tumour necrosis rate showed a significant correlation in long-term survival in Osteosarcoma (6). The EURAMOS-1 study reported that those patients, who had a poor histological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, were associated with worse survival outcomes post-surgery (7). The treatment modalities for pulmonary metastatic lesions showed significance in the improved survival of osteosarcoma patients. For osteosarcoma patients with resectable lung metastasis, the NCCN guidelines recommended wide excision of the primary tumour and preoperative chemotherapy (8). Meanwhile, pulmonary metastasectomy option could be of consideration in selected patients. It had been reported that patients with fewer lung lesions, unilateral lung disease and patients post metastasectomy had shown improved survival compared to the rest (9). With the concurrent prediction of survival and benefit versus anticipated complications from metastasectomy on lung function improvement, metastasectomy should be encouraged in eligible and selected patients only. Lung metastasis occurs most frequently over the first 2-3 years from diagnosis. Patients with higher risk factors should be given more attention. Previous studies had suggested more lung metastases and bilateral lesions involvement in patients after surgery of primary tumour alone, compared with those with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (10).

There are significant limitations to this study. Due to the unequal duration of follow up & poorer patient compliance from diagnosis to treatment to follow up, some patients were lost and could not be reached. The limited sample size and unknown information in some variables caused uncertainty in data statistics. Especially on the fact that the 5-year period of the data was overlapping the 2 years COVID period, where patients were lost from follow up and travel restrictions leading to the significant drop in the volume presenting to the institution for consultations. Furthermore, the limitation of the retrospective study design also leads to weakness in drawing any confirming conclusions besides statistical data analysis.

Conclusion

In summary, Osteosarcoma patients in our institute were effectively treated in accordance to national guidelines, in a 5-year overall statistics. The incidences of synchronous and metachronous lung metastasis were high. The prognostic factors found in the current study cannot be predictors of significance on survival. Risk factors of lung metastasis can be used to identify high-risk patients and guide individualized screening. Accurate and effective diagnosis, preoperative chemotherapy, surgical resection, postoperative chemotherapy, and life-long monitoring are critical factors involved in successful management of this complex and potentially fatal disease. More research is needed on the cause of osteosarcoma and its progression, the role of genetics, better testing options for earlier and more accurate diagnosis, and treatments that can reduce patient morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Mr (Dr) Aaron Gerarde Paul – Orthopedic head of state and Orthopedic Oncology surgeon in Sabah Malaysia since 2013: that had started services for the subspeciality here in Sabah. Also gratitude to the institution, Hospital Queen Elizabeth 1 & 2 for the effort on starting Oncology services and safekeeping of patients data. Acknowldgement to the pathologist that had reported and analysed the pathology component. Along side Mr (Dr) Tee Kok Keat that had along side me authored this paper.

Reference

1. Vasquez L, Tarrillo F, Oscanoa M, Maza I, Geronimo J, Paredes G, Silva JM and Sialer L (2016) Analysis of Prognostic Factors in High-Grade Osteosarcoma of the Extremities in Children: A 15-Year Single-Institution Experience. Front. Oncol. 6:22. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00022

2. Bacci G, Ferrari S, Bertoni F, Ruggieri P, Picci P, Longhi A, et al. Long-term outcome for patients with nonmetastatic osteosarcoma of the extremity treated at the Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli according to the Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli/osteosarcoma-2 protocol: an updated report. J Clin Oncol (2000) 18:4016–27.

3. Leissan R. Sadykova, Atara I. Ntekim, Musalwa Muyangwa-Semenova, Catrin S. Rutland, Jennie N. Jeyapalan, Nataliya Blatt & Albert A Rizvanov (2020) Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Osteosarcoma, Cancer Investigation, 38:5, 259-269, DOI: 10.1080/07357907.2020.1768401

4. Michael J. Klein, Gene P. Siegal, Osteosarcoma: Anatomic and Histologic Variants, American Journal of Clinical Pathology, Volume 125, Issue 4, April 2006, Pages 555–581, https://doi.org/10.1309/UC6KQHLD9LV2KENN

5. T. Taupin, A.-V. Decouvelaere, G. Vaz, P. Thiesse, Accuracy of core needle biopsy for the diagnosis of osteosarcoma: A retrospective analysis of 73patients, Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging, Volume 97, Issue 3, 2016, Pages 327-331, ISSN 2211-5684, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2015.09.013.

6. Zhang, C., Wu, H., Xu, G. et al. Incidence, survival, and associated factors estimation in osteosarcoma patients with lung metastasis: a single-center experience of 11 years in Tianjin, China. BMC Cancer 23, 506 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11024-9

7. Smeland S, Bielack SS, Whelan J, Bernstein M, Hogendoorn P, Krailo MD, et al. Survival and prognosis with osteosarcoma: outcomes in more than 2000 patients in the EURAMOS-1 (European and American Osteosarcoma Study) cohort. Eur J Cancer. 2019;109:36–50.

8. Biermann JS, Chow W, Reed DR, Lucas D, Adkins DR, Agulnik M, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Bone Cancer, Version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(2):155–67.

9. Gao E, Li Y, Zhao W, Zhao T, Guo X, He W, et al. Necessity of thoracotomy in pulmonary metastasis of osteosarcoma. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(8):3578–83.

10. Goorin AM, Shuster JJ, Baker A, Horowitz ME, Meyer WH, Link MP. Changing pattern of pulmonary metastases with adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with osteosarcoma: results from the Multi institutional osteosarcoma study. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(4):600–5.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8