Knee Injuries caused by Collateral Ligaments

Knee Injuries caused by Collateral Ligaments

Pratham Surya1*, Dr Apoorva Sharadrampure2, Dr Vivekananda Patil3

*Correspondence to: Pratham Surya, Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon.

Copyright

© 2024 Pratham Surya. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 12 Sep 2024

Published: 01 Oct 2024

Knee Injuries caused by Collateral Ligaments

Introduction

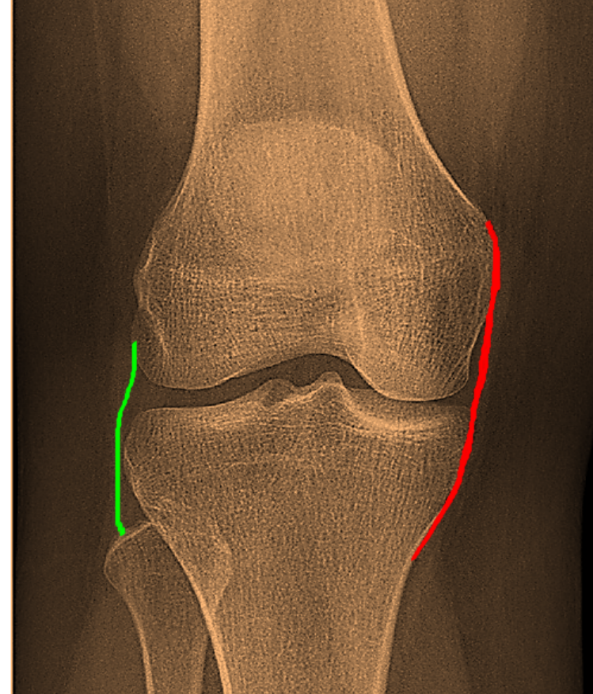

The two ligaments in the knee: the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). Medial ligament injuries are most often caused by impact to the outside of the knee, called valgus forces. Ligament injuries can occur alone but are often associated with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and/or posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injuries. Gender: Described as two matchsticks held together by rubber bands. These "rubber bands" are four major ligaments: two cruciate ligaments, the anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament, and two accessory ligaments, the medial and lateral ligaments (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Schematic AP drawing of the medial (red) and lateral (green) collateral ligaments.

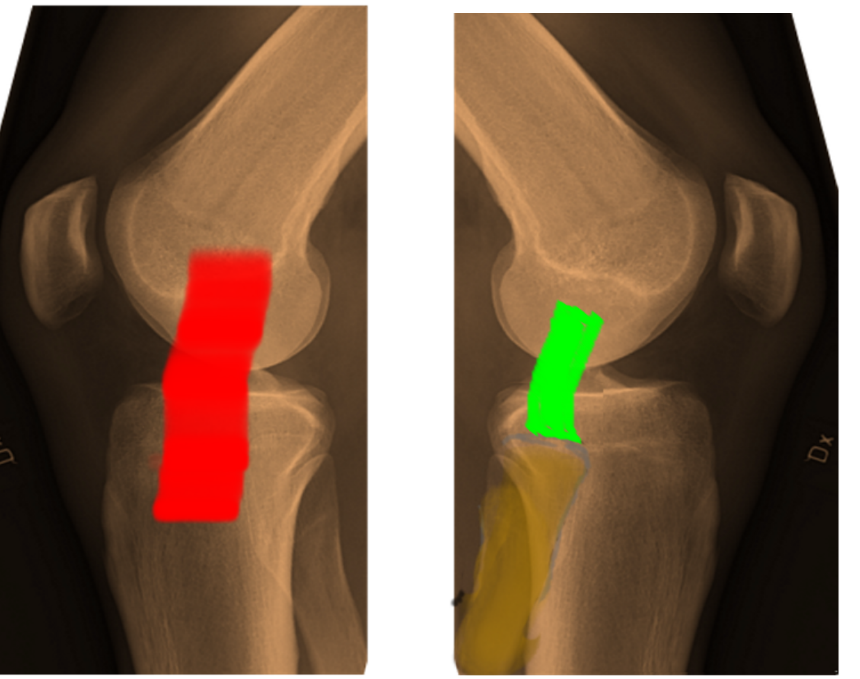

Figure 2: Schematic lateral drawing of the medial (red) and lateral (green) collateral ligaments.

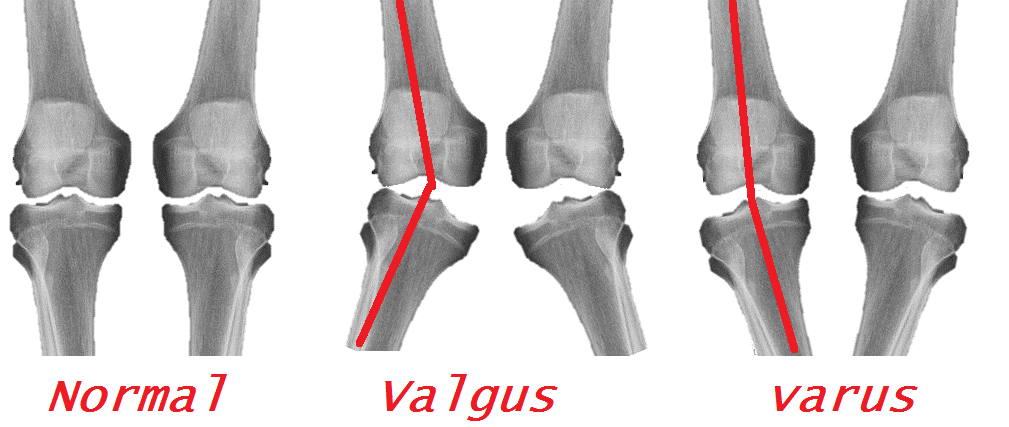

These ligaments work together to stabilize the knee. Other soft tissues such as the capsule and menisci also help provide stability. In general, the cruciate ligament prevents the tibia from displacing anteriorly or posteriorly relative to the femur and provides side-to-side stability to the leg. The deforming force created by blowing on the outside of the knee. The MCL also works with the ACL to prevent axial rotation of the knee. The MCL originates at the medial epicondyle of the femur, inserts into the medial aspect of the tibia, and continues downward for several centimeters. The deep fibers of the MCL extend to the medial meniscus and are separated from the superficial fibers by a bursa. The posterior fibers of the deep MCL blend with the posteromedial capsule and the posterior oblique ligament. MCL can withstand up to 4000N of force without tearing. Deformity of the midline; Varus refers to deformity from the center to the middle. This term is often used in connection with the knee. leg". As seen in Figure 3.)

Figure 3: A normal alignment of the knee to the left; valgus in the middle; and varus to the right.

The LCL itself is smaller than the medial collateral ligament. It originates from the lateral epicondyle of the femur, from the posterior, upper and superficial part of the insertion of the popliteus muscle. The LCL inserts anteriorly on the popliteofibular ligament (PFL) on the superior fibula. The LCL strength was measured at a tension of 750N. Lateral stability is provided by the popliteus muscle and tendon and a group of ligaments called the “posterolateral angle.” Pain may be felt on the medial side of the torn ligament; pain will be felt on the side of the injury or where the femur and tibia are bruised; overall, there is only difficulty walking and a sense of instability in the knee. There may be tenderness on palpation. Ecchymoses may also be present. The knee may or may not contain fluid. When the medial ligament is completely torn, fluid may not be present because the torn tissue allows fluid to accumulate in the joint. Degree of knee joint flexion (Figure 4). When extended, the capsule provides additional stability to cover a lower MCL injury. If the difference occurs in continuity, consider a compound injury. A complete tear is defined as a difference of more than 10 mm or an increase in valgus angle of more than 10 degrees. Grade II sprains are characterized by plastic deformation of the ligament, with some gaps, but less than 10 mm. The saphenous vein should be assessed by examining the sensation in the mid-calf and palpating the popliteal and distal veins of the foot.

The stability of the varus forces was also assessed by attempting to repeat the same procedure with the knee joint in 30 degrees of flexion. The forces that deform the varus exert traction on the arteries; it is important to perform a detailed physical examination, including vascular examination, in these patients. If there are multiple ligament injuries, the knee will dislocate or sublux. The incidence of popliteal nerve injury in knee dislocations is approximately 50%.

After a thorough vascular exam, sensation should be assessed distinctly in the tibial, deep peroneal and superficial peroneal distributions. Motor examination should include flexor and extensor hallucis longus, tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius to establish baseline. The incidence of nerve injury ranges from 4.5% to 40%. The most commonly affected nerve is the common peroneal nerve, however isolated tibial nerve palsy has been reported.

Patients with some arthritis can present with a slight laxity on valgus stress testing with an intact medial collateral ligament. This is known as pseudo-laxity. The phenomenon is produced by the loss of articular cartilage causing narrowing of the medial joint space, which can then be corrected by the application of an external force.

Objective Evidence

For a patient presenting with a knee injury and possible ligamentous damage, radiographs with anteroposterior and lateral views are indicated.

Medial or lateral widening suggests possible ligament disruption. Considering that stress x-rays could worsen a partial ligament injury, they are not advised – especially since they are not apt to change the acute care management, and MRI can provide the same information, if not more.

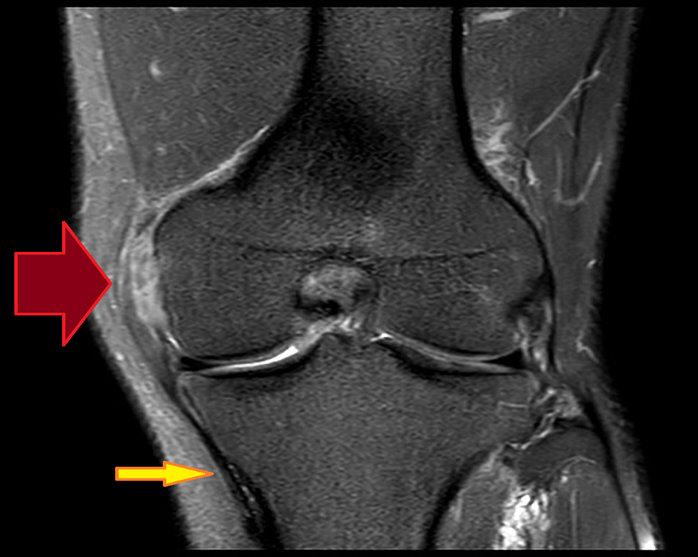

For acute knee injuries, an MRI is extremely helpful. An MRI can provide information about severity (complete vs. partial rupture) and location (avulsion vs. mid-substance tear). Of course, an MRI will also pick up associated injuries. For chronic conditions, it may be helpful to employ an MRI if and only if the anticipated results of the test will dictate management (Figure 4).

Figure 4: An MRI showing a high grade MCL tear proximally (red arrow). The yellow arrow points to intact ligament distally.

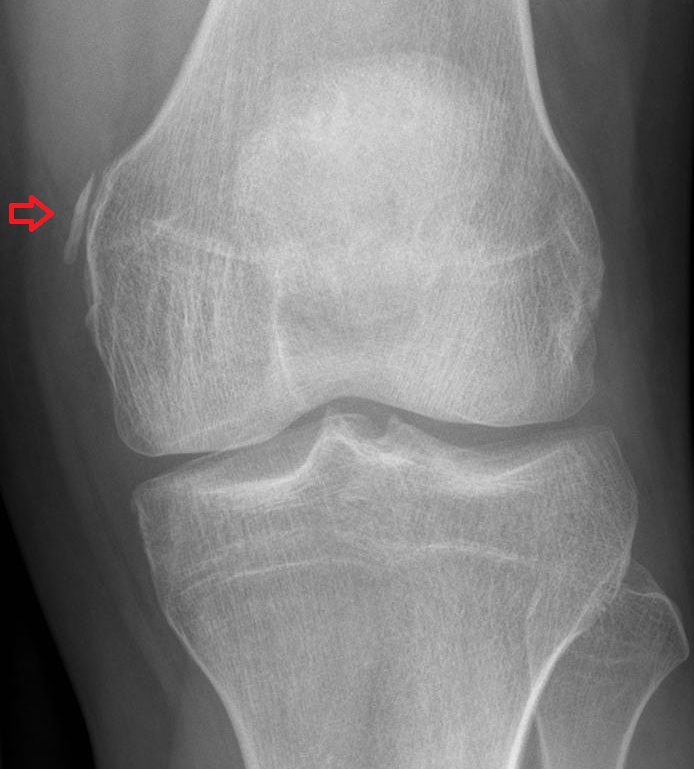

With chronic MCL injuries, calcification at the medial femoralinsertion site may be seen. This is known as a Pellegrini-Stieda lesion (Figure5).

Figure 5: A Pellegrini-Stieda lesion. A sliver of calcification is shown by the arrow.

Epidemiology

Collateral ligament and multi-ligamentous injuries can occur in a variety of mechanisms thus leading to a very diverse patient population who suffer from these injuries. The most commonly injured ligament of the knee is the MCL.

Isolated injuries to the LCL are very rare. Injuries to the LCL are almost always found in combination with injuries to other ligaments, particularly posterolateral corner (PLC) injury.

Multi-ligamentous knee injuries most often occur as a result of high energy trauma, and perhaps due to gender differences in activities and risk seeking behaviors, are predominantly found in males. Low energy injuries that lead to multi-ligamentous knee injuries are almost exclusively limited to the obese population.

Differential Diagnosis

In addition to the collateral ligaments, the cruciates, the menisci, the extensor mechanism and the articular surfaces might be damaged by a sports injury. It is especially important here to remember the veterinary maxim ‘a dog can have both lice and fleas’, meaning the discovery of one injury does not signify the end of the examination as combined injuries are commonly seen.

In pediatric patients with open growth plates (physes), it is important to note that the MCL is typically more robust than the distal femoral physis, and thus, more resistant to injury. A suspected MCL tear in a patient with an open distal femoral growth plate, therefore, is more likely to have a physeal injury (fracture) than an MCL sprain and this may warrant a different treatment strategy.

Injury to more than one ligament suggests the possibility of injury to the popliteal artery or common peroneal nerve.

A loss of passive range of motion suggests interposed tissue (such as a piece of meniscus or articular cartilage). Another possible cause of blocked motion is “button holing” of the femoral condyle through the capsule. This finding is a clue to a more severe injury.

Treatment Options and Outcomes

Because it is extra articular, the medial collateral ligament has good healing potential. Placing the patient in a brace can stabilize the knee and allow the ligament to heal at the appropriate length. Indeed, even if surgery is needed for other ligament injuries, it may be reasonable to allow the MCL to heal first.

Once some healing has taken place, physical therapy for quadriceps and hip adductor strengthening is indicated.

Operative repair may be considered for complete (Grade III) tears especially in the setting of multi-ligament knee injury. Another indication for surgery is if there is a displaced distal avulsion present–that is, if the MCL pulls off its tibial attachment. Surgery is needed because if the distal MCL retracts proximally, the pes anserine tendons will block healing.

For chronic injuries, or when there is loss of adequate tissue for repair, a reconstruction with either allograft or autograft is performed.

Treatment of LCL injuries is usually dictated by the presence of any associated injuries.

Most people with injuries to the medial collateral ligament will make a good functional recovery, but may require three months to get there.

Outcomes of LCL injuries are usually dictated by the response to treatment for the associated injuries.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for ligament injuries of the knee include participation in sports and obesity.

In high performance athletes who were unwilling to not play, the risk of MCL injuries (or worsening of an already present mild injury) may be mitigated by functional bracing.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5